Food Logistics-led Urbanization

Mass Market Retailers’ Distribution Centers in Italy

Year

2021 – 2024

Author

Supervisors

Departments

DIST

Tags

#Logistics #FoodDistribution #workspaces #urban transformations #infrastructures

Type

PhD research

Abstract

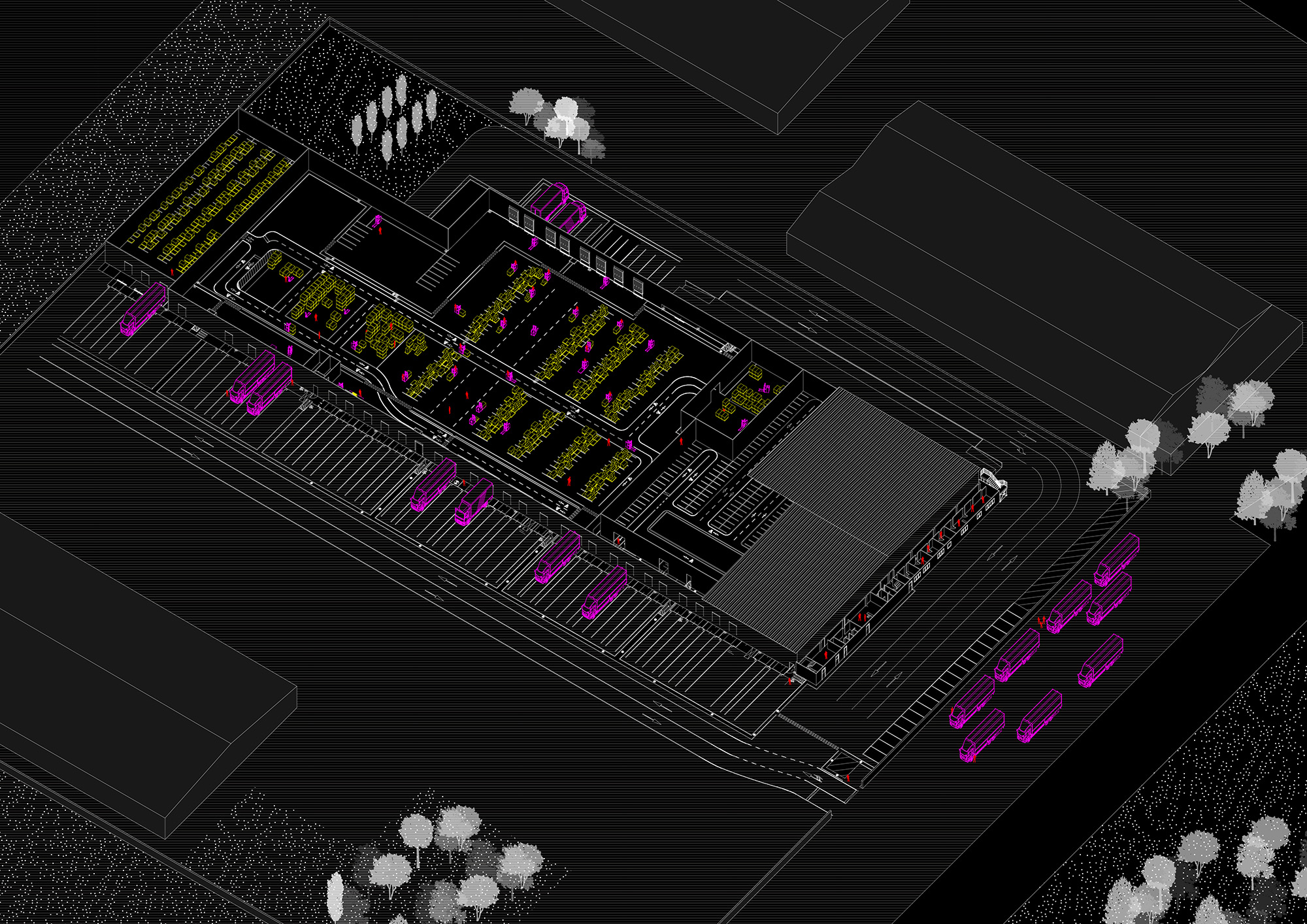

Over the past two decades, the logistics of food distribution have undergone radical transformation processes, primarily aimed at increasing performativity. This has taken place through logistical refinement, technological advancement and increasing automation throughout the supply chain. In this framework, in Italy, a fundamental role is played by the Mass Market Retailers (MMR, in Italian GDO) that, in the last decade, have opened hundreds of Distribution Centers (DCs) located in strategic areas to serve their stores.

Considering the technical processes that regulate these spaces, as well as the relationships with multi-actor and supranational economic and logistic systems, the wide literature that deals with them tends to privilege observations aimed at their decontextualization and extra-territoriality. To the point of recognizing in them the nodes of a global network, an automated ‘technopoly’ capable of functioning without a human being.

Although this dimension is certainly relevant, the research aims at showing how Distribution Centers are now spaced strongly linked to the territories within which they have been implanted, and how over time they have built economic and social relationships progressively more complex and durable.

In support of this thesis, in the research, I investigate about ten Distribution Centers of several MMR companies, located in three case study areas. These are selected among sites with a high logistics density, thus becoming distribution hubs at the regional and national levels.

On the one hand, the research seeks to build a solid theoretical framework that situates distribution centres primarily within urban studies of the logistics world. On the other hand, mainly through fieldwork, I seek to explore numerous aspects of DCs, focusing on the physical dimension of the places, the technical-functional dimension, the working conditions of the employees and the economic and social dynamics that the centres to determine and modify at the local level. The functioning of these spaces conveys specific forms of urbanity. The research intends to support how these forms require precise and relevant investigations, descriptions, and interpretations, capable of grounding the DCs in the territories in which they are located. Thus, capturing the importance of local relationships, the implications on mobility, housing, the redefinition of the relationship between space, automation, and human. Such an interpretative framework can help to relocate distribution centres within a more complex network of relationships, not just at the supra-local level. For this reason, it suggests the need to activate new policies and new projects.