Loft Working

Basic observations on urban manufacturing spaces in North American cities

The research observes the shaping of urban manufacturing activities in some of the major North American cities.

Urban manufacturing has made its way through often-unprepared cities, in terms of policies and regulations, reusing spaces disregarded by mainstream real estate and commercial trends. Urban manufacturing reduces different building typologies into lofts; open, generic, rough and flexible spaces defined by their capacity in terms of space, location and infrastructure rather than a form or a function. Firms expand the capacity of lofts and adjust them to their needs through a series of spatial actions and architectural devices.

The research defines this trend as loft working. By being affordable, disposable, distributed and flexible, lofts have been the supporting system of urban manufacturing dynamics that move within fuzzy boundaries of formal/informal, public/private, global/local, temporary/permanent, non-profit/for-profit. These compelling dualities represent an opportunity for cities to take a step forward in their effort to address increasing complexity, diversity, inequalities and rapid changes.

Year

2019

Author

Tags

#Architecture #NonPerformingLegacies

Type

PhD research

abstract

Urban manufacturing is the ‘oldest, newest thing’ going on in cities. It proceeds from the evolution of the oldest and the newest development of cities and industry. In the North American context, industry emerged contextually as rural and intra-urban trend. Rural areas soon turned into suburbs, thus making industry a metropolitan issue made of urban and suburban locations. After becoming a predominantly extra-metropolitan matter for a long time, manufacturing has also re-emerged as a metropolitan and urban trend. Urban manufacturing has taken shape within urban areas as a dense network of small/medium enterprises that operate in supple, peer-to-peer, decentralized networks of research, development, production, assembly, and distribution.

For long, ‘reindustrialization’ narratives have focused on retaining large-scale standardized manufacturers, for whom it makes no sense to stay in cities. But innovation and economic trends move at a much faster pace than the physical city. When the attention on urban manufacturing finally arose, it revealed a plethora of unplanned or overlooked forms of making that had already made their way into an often-unprepared city through the reoccupation of vacant spaces. Different forms of production superpose and reshape the physical legacy left behind by the course of different economic trends and industrial paradigms. A first wave of reuse for production roots in the 1980s when cities were progressively oriented toward service economies. Then, a second wave emerged in reaction to the Great Recession, along with the spreading of technological innovations that have been consistently disrupting industrial and economic paradigms. What started as a last attempt to endure in cities by firms increasingly pushed to the fringe, it has then turned into a strategic choice.

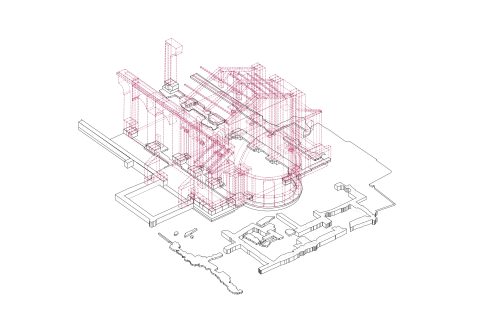

Today, firms set their workspace inside leftover buildings to take advantage of the contextual opportunity for a good location, access to affordable spaces, and renting rather than buying or building new – hence ensuring more flexible commitments with one location as well as investing fewer resources in space. Urban manufacturing firms can usually adjust to almost any lofty space with no special requirements: the physical space remains determinant, but it has to weigh as little as possible in economic terms in favor of innovation, knowledge, and location. Also, the transition to a factory intended as a digital object has accelerated the trend.

Urban manufacturing reshapes urban contexts in two steps. First, it reduces different building typologies into left-as-loft spaces able to adapt to a wide variety of economic and human activities. Lofts are open, generic, rough, and defined by their capacity in terms of space, location, and infrastructure – rather than a form or a function. Then, lofts are reconfigured as working lofts. Firms project and adjust their production process into the real space through a series of spatial actions and architectural devices that expand loft’s capacity, both in its performance and quantity. By being affordable, disposable, occasional, distributed throughout metro areas, and diversified in their capacity and potentials, lofts have been the supporting system of urban manufacturing dynamics that move within fuzzy boundaries of formal/informal, public/private, global/local, temporary/permanent, non-profit/for-profit.

Loft working heads towards multiple resolutions: reactivating a latent structure by turning it into a flexible and adaptable empowering tool (the loft); giving space to income- and job-generating economies (urban manufacturing); reconnecting a lost piece of the urban fabric with the city’ and metro’s socio- economic dynamics (placemaking). A process still under development that cities would be able to fully capture and take advantage from only through undetermined and unfinished strategies.