Contemporary Rentscapes

Transformative strategies for large rental housing stocks

Contemporary Rentscapes is a biennial research project funded by Sidief Spa (Bank of Italy), focusing on transformative strategies for large rental housing stocks.The first part of this project was published in the book Re-Housing, ‘La casa come dispositivo di integrazione’ (The House as an Integration Device), (Polytechnic University of Turin, 2018). Triggered by the need for a generational turnover of the urban tenant, FULL demonstrated the flexibility of a portion of early twentieth-century housing stock through a toolkit of micro interventions. The second iteration of the project (Living beyond Property) investigates the innovative global offer on the private rental market, mapping and decoding the patterns and connections between private and public space in the serviced domestic realm.

Year

2017-2019

Scientific coordinator

Research coordinators

Collaborators

Caterina Quaglio, Davide Rolfo, Lorenzo Rabagliati, Giulia Ravera

Funding

Sidief Spa

Tags

#Architecture #NewHousingIssues

Type

Research project

The project

Contemporary rentscapes is a biennial research project funded by Sidief Spa (Bank of Italy) focusing on transformative strategies for large rental housing stocks.

The first part of this project was published in the book Re-Housing, la casa come dispositivo di integrazione (The House as an Integration Device) (Polytechnic University of Turin, 2018). Triggered by the need for a generational turnover of the urban tenant, FULL demonstrated the flexibility of a portion of early twentieth-century housing stock through a toolkit of micro interventions. The second iteration of the project (Living beyond Property) investigates the innovative global offer on the private rental market, mapping and decoding the patterns and connections between private and public space in the serviced domestic realm. This section of the project will be published in the book Abitare oltre la proprietà (Living beyond Property) (Polytechnic University of Turin, 2019).

Re Housing (2018)

Can housing serve as an enabling factor to integrate new citizens?

On 8th August 1991, the ship Vlora landed 20,000 Albanians on Italian shores. Since then, a lot has changed.

During the last twenty-five years, immigration from a wider and wider spread of foreign countries has coincided with radical cultural and economic transformations in Italy. The social fabric in Italy has been deeply changed by the interaction between different cultures.

This mutation has not been compensated for by a significant renewal in the built environment, historically characterised by an inertia towards inflexibility. The progressive mutation of life conditions of Italy’s new residents is leading their housing demand to increasingly converge with that of more and more Italians. This unexpressed potential can be reimagined today as a resource to forecast strategies of renewal in the existing urban fabric and build a common ground, a place of sharing and integration.

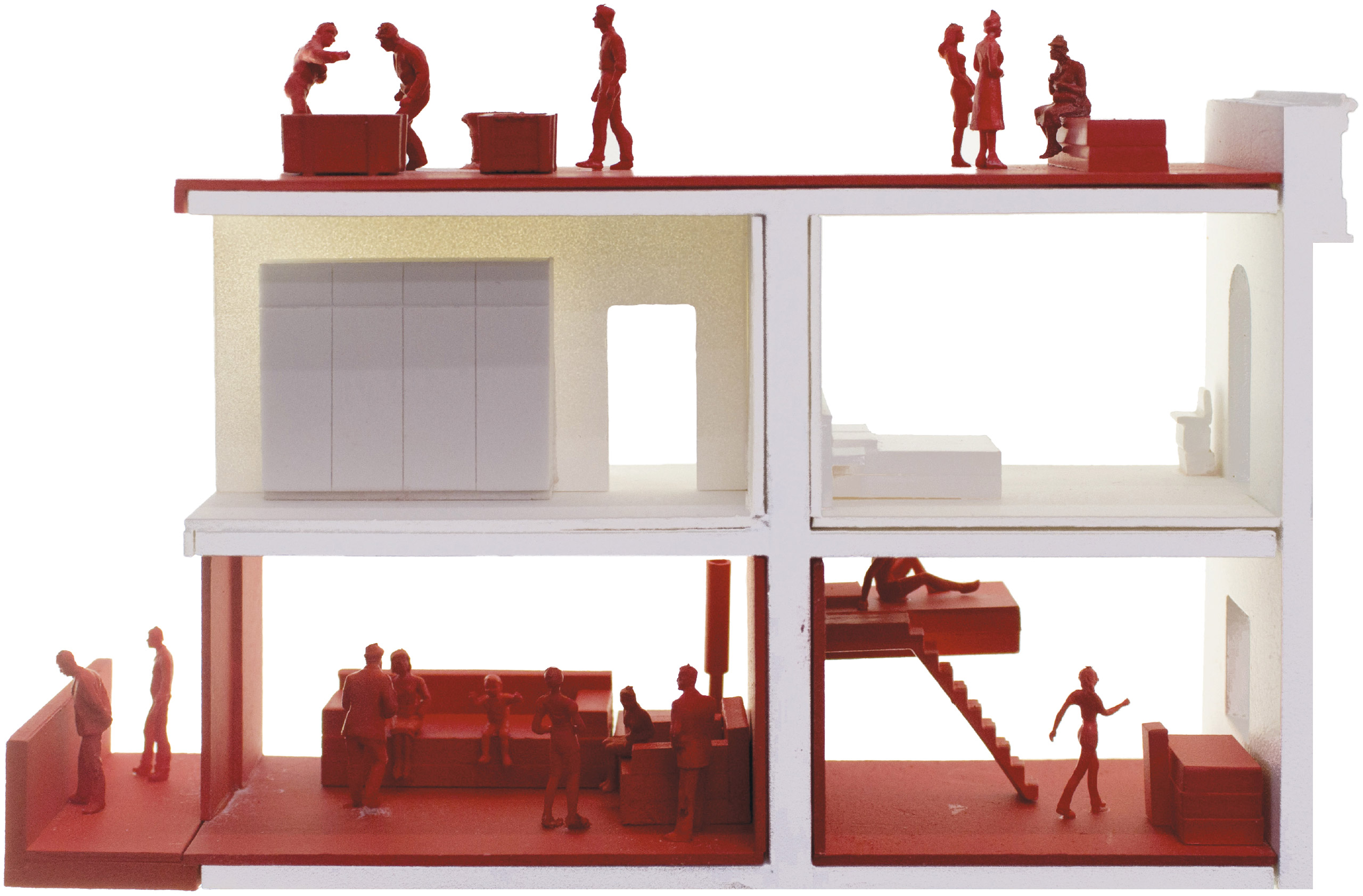

Integrating housing with the city’s new technological services and housing models today opens up the possibility of externalising much of the infrastructure embedded in the domestic unit. This phenomenon not only allows new housing typologies to be conceived, but also allows a portion of the existing housing stock to be radically transformed. The traditional housing models, characterised by a rigid and inflexible compartmentation, can be redesigned into flexible, open systems thanks to the application of new spatial strategies and new management tools. Transforming under-utilised rooms in new collective spaces and organising innovative management systems allows a new conception of housing to be formulated. A new form of housing able to meet the demand of new Italians.

From specialised housing towards an original policy

The Italian city, with its sheer quantity of public space and high-density urban blocks, has for centuries represented an efficient model of integration between the individual and the collective dimension. This model, which in the recent past has seemingly been replaced by a sprawl of detached houses, is today becoming an actual one infilled with new ways to live and new conceptions of inhabitation of the private and public spaces of the house. New housing typologies, developed inside dense portions of the city, allow innovative forms of integration between the private and the public dimension. The porosity of a densely-built city, subdivided in its core by a fragmented private property structure, represents the fertile ground to develop a system of housing and services distributed in the city in an efficient network instead of a one-size-fits-all model.

Living beyond property (2019)

Italy is a country of homeowners. However, according to national statistics, cash renters do not seem disadvantaged in relation to their landlords: 9 million tenants spend on average €400 per month on their rent (only 14% of the average national income). In major cities, these figures change radically. In the case of Milan, the affordable rental flat area is about 30 m2 – the area corresponding to 30% of median rent over the median city income –, while the median area of rental flats in the city is 70 m2.

Cities are the place where Engels’ Wohnungsfrage has always unfolded in its more severe form, historically in purpose-built housing typologies like Berlin’s Mietskasernen, the tenements of New York and the Parisian immeubles de rapport.

In post-war Europe, the deprived social conditions associated with these typologies triggered experimentation in the field of social housing, assigning to the state also the role of great landlord. The mass provision of housing led to the dimensional standards still in use in planning regulations.

Paralleled to this mainstream story, some housing typologies were designed and optimised based on human body dimensions. The hotel, from its first conception at the end of the 18th century in the United States, has always been an incubator for domestic innovation.

Today, if we observe major cities across the globe, we find hybrid housing typologies, mixing the spaces and services of the hotel with the notions of comfort and security typically associated with the traditional rental flat. Rental housing in this sense operates simultaneously as a dwelling and as a constellation of included services. Units of reduced size are combined with common areas and facilities in single buildings. Plus, housekeeping service and hotel-like management are usually included in the rental fee. Depending on budget and target users, this can take the form of co-living for students and professionals, luxury or branded apartments, serviced apartments and apartments for elderly people.

What would be the consequences of a city where no-one owns a home, but everybody can rent a house?