Poseur Real Estate

Home staging as an enabling commodification practice

Housing commodification is one of the contemporary phenomena inscribed in the deregulated, financialized, and globalized housing system. Today’s hyper-commodification refers to housing as an instrument of financial accumulation, enhancing the divide from its residential function.

A relatively new business active within the rental housing market is the so-called home staging. Comparable with an interior design service, home staging means literally to set-up the domestic environment. It gathers a set of professional and non-professional actors involved in the re-furnishing and re-adaptation of the shelter for commercial purposes, enhancing new aesthetic standards. Indeed, this new model is applied and then showcased in the short-term rental market. More than others, Airbnb developed a strict aesthetic-commercial model, a combination of Scandinavian minimal wooden furniture in a white-box-like dwelling that can be summarized in the Danish word hyggelig.

The digital revolution triggered a crucial paradigm shift in terms of actors involved, practices, production of values, and transfer. The digital space is the new space of capital fluctuation, and thus, it is a critical matter when it collides with staple goods such as housing.

How does the tech-mediated market enact a progressive dissolution of the private domestic space into a staged commodity?

These new tactics adopted from the market highlight the shift in contemporary real estate operators’ rhetoric from the concept of housing to the one of living. In this context, the experiential (staged) features of a domestic scene overcome the typical real estate triad of location, location, and location in housing promotion.Drawing on a taxonomy of contemporary experiences, the paper will investigate the mutated concept of standard. Once linked to representativeness and now projected towards representation, the new standard set by home staging allows landlords to maximize value extraction from the short rental market, marginalizing further the real economy of dwellings within the city.

“I think that idea of commodifying your environment or turning everything into a purchasable object, that seems likely to happen”1

Mark is a property manager based in Copenhagen. He entered the business of home-sharing after a shocking and revealing episode. During his first experience as an Airbnb host, Mark realized that his guests used his clothes and the ones of his wife to share videos on social media under the hashtag #weirdsex. Horrified, he installed spy cameras in his house to control his guests during their stays. After a while, he figured out that more and more guests were using his home to act and perform as characters –literally– in the shoes of someone else. Mark reacted drastically. He deleted his real identity from all social media, quit his job, and created several fake host profiles to rent on housing platforms houses sublet by a real estate agency. He bought on a specific website photographic sets of daily life portraits made by professional actors. Then, he set the house as it if was inhabited by the characters portrayed in the pictures –the fake hosts. In an interview released to Beka & Lemoine in their documentary Selling Dreams, Mark stated that he was fulfilling a precise market demand: “They wanted to have another life, another story, to be other characters for few days. […] It’s not fake, it’s true if you believe in it.”2

In 1967 Guy Debord wrote The Society of Spectacle, referring to the dominance of the culture of images as a developing form of the concept of alienation, structuring a Marxist critique to the life-pervasive commodification. During the last century, the power of images strengthened at the point to become nowadays the channel in which profit chains can express and reproduce themselves.

The role of images and the production of imaginaries are at the base of the advertisement and consumption process. The rapid rise of new economies, mostly acting in the digital space, allowed a fast and capillary spreading of the culture of image and, consequently, a pervasive process of commodification. In this article, we discuss the role of images as a commodifying tool lead by digital platforms in the housing market. Questioning, how does the tech-mediated market enact a progressive dissolution of the private domestic space into a staged commodity.

Residential property constitutes the first asset class globally in terms of value, representing 60% of the worlds’ wealth, including stocks, bonds, and gold3. This condition resulted from a half a century process, where the real estate market mutually fed itself with the neoliberal state ethos of the property-owning democracy, leading to what Samuel Stein defines the Real Estate State4.

In this context, the residential function of housing is subject to its value as an asset. Nevertheless, this dual and contradictory condition is embedded in any commodity since Marx stated the coincidence of the use-value and exchange value of the commodity5.

Therefore, trading of housing as a commodity is nothing new, while referring to the commodification of housing refers to the progressive growth of a large part of housing production and consumption aimed only at speculation, not even contemplating inhabitation. As Hellinikon, the massive development project in Athens, where the developers on a total of 260 hectares of development, provided not even a square meter of social housing6.

The effects of hyper-commodification7 are palpable in major western cities as New York or London, where the scale of investments is such that the housing prices might be unaffordable for the majority of the urban population8. Hyper-commodification of housing unfolds in terms of social exclusion and depopulation. Plus, commodification penetrates the multi-layered urban fabric beyond the real estate market. As noted by Forrest and Williams already in the 1980s, “in understanding the full implications of this commodification process, we must begin to comprehend the way these changes penetrate into the very fabric of daily life”9. A similar argument is carried out by Randy Martin in his book of 2002 Financialization of Daily Life, in which he highlights how the contemporary economic structure of self-entrepreneurship could modify the financial borders widely, letting them flood into the private sphere.

Such dynamics are recognizable –among others– in the sharing economy’s mechanism, in which companies make profits by financializing everyday life activities or jobs formerly protected by corporations. UberEats monetized cycling, carpooling apps as CarToGo converted motorists in taxi drivers, and TaskRabbit can now sell housekeeping services without any professional or insurance coverage. This marketplace also includes the domestic sphere, as companies of furniture design, property management, and renting complete the full spectrum of commodified aspects of domestic daily life.

Notes

-

1

Bava A., Branzi A., Yu R., Harvey A. T., (2014) “Everything that is solid melts into Airbnb”, Panel, Aribnb Pavillon, https://www.swissinstitute.net/event/panel-everything-that-is-solid-melts-into-airbnb-with-alessandro-bava-andrea-branzi-rachael-yu-and-aaron-taylor-harvey-of-airbnb-hosted-by-airbnb-pavilion-fabrizio-ballabio-alessandro-bava-luis/ [1/06/2020]

-

2

Beka, I., & Lemoine, L. (2016). Selling Dreams [Documentary]. Beka&Lemoine. https://vimeo.com/ondemand/sellingdreams/189505421 [1/06/2020]

-

3

The real estate market is worth about 217 trillion of US dollars, almost “60 percent of the value of all global assets, with residential real estate comprising 75 percent of the total”. Farha (2018).

-

4

Stein, 2019.

-

5

As David Harvey critically analyzed (2018).

-

6

https://thehellinikon.com/the-vision/. [15/05/2020].

-

7

Madden and Marcuse, 2016.

-

8

For New York see Stein 2019. For London see Minton 2017.

-

9

Forrest and Williams 1984: 1178.

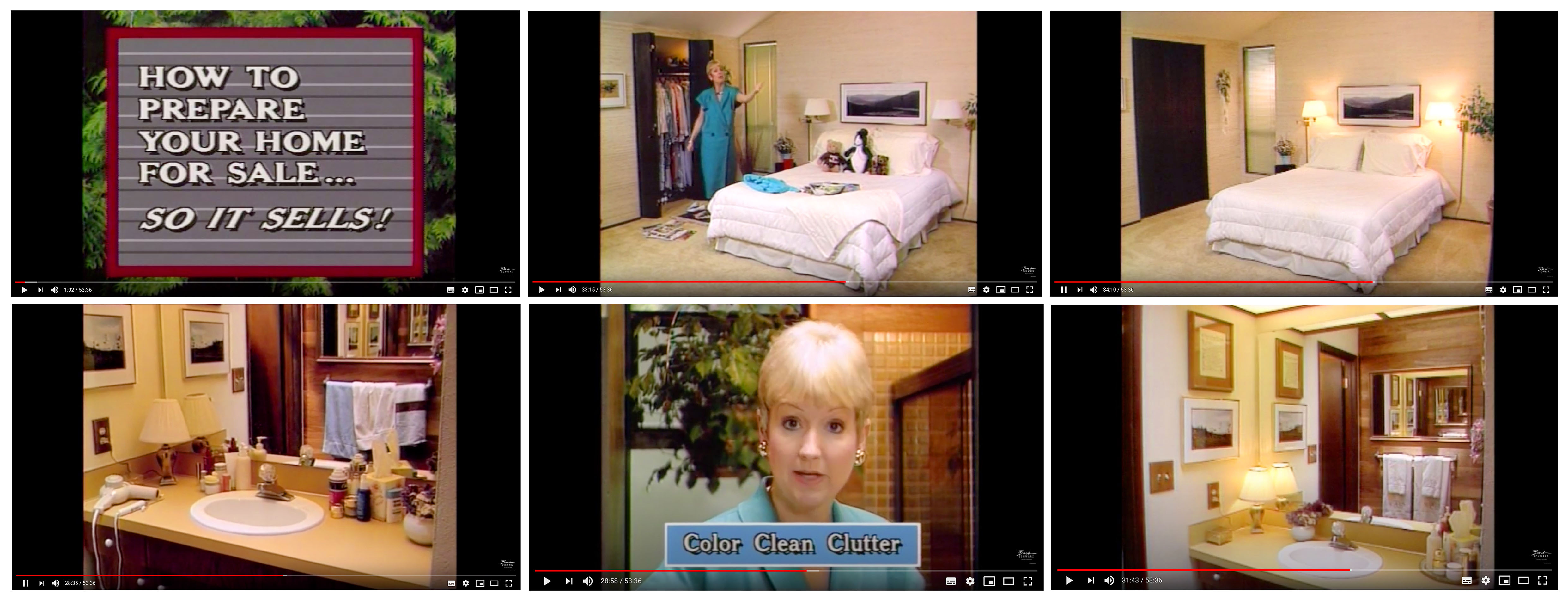

“How to prepare your home for sale…so it sells!”10

Airbnb –the major short-term rental platform currently available– has revolutionized the hospitality and housing market since its inception in 2009. As for all the Silicon Valley tech companies, the funding and evaluation system of venture capital defines Airbnb’s performance. Nevertheless, disregarding the downturns of the market, what Airbnb introduced was a concept enabling potentially the global commodification of any single housing unit around the world –including tree houses and boats.

It is important to note that in its early days Airbnb was not even conceived as a service for payment, following the example of websites like Craigslist or Couchsurfing, which based their profits on indirect revenue from advertisements and external funding. This highlights how the platform economy is even less attached to the value generated from the use of its products instead of the mass of data that it generates. This reading shared by Nick Srnicek in his book Platform Capitalism,11defines a taxonomy of the different typologies of platforms currently existing. Airbnb falls in the “lean platform” category, as it generates revenue from housing rents without actually owning none of its listings.

The other disruptive innovation introduced by Airbnb is one of the keys to the success of most platforms: reputation12. Any host and guest of an Airbnb has to submit a detailed review, which automatically fits any single listing in a given market. Coherently with Srnicek reading, the real asset that platforms produce is data. Reputation is built upon a certain critical mass of data stored on the product, as the number of reviews (and visits), the quality of its service, and its amenities. Major the number and the better the reputation, the higher the price. A crucial aspect of this phenomenon is that a consistent part of the data used by Airbnb to sell its product is pictures of the listings. Differently from the traditional hospitality sector that has a codified standard-setting –think of the stars of a hotel –, Airbnb relies significantly on the effectiveness of its photographic apparatus13.

This fact complexifies the comparative evaluation of two “equivalent” market products greatly, bypassing most of the traditional mantra of real estate: location, location, location.

On the other hand, this element of complexity justifies the massive initial effort of the company to provide free photo shootings to hosts14, since once collected the interior photos of the listings were not only showing a determined quality, but they sold a “genuine” product. If we take the sales and promotion process of ordinary real estate, we will find a sheer amount of interior renderings realized by professional CGI companies to enable the developer to sell upfront its buildings before completion. These interiors are usually populated by high-end furniture design objects that are present in 3d model libraries of the major digital companies of the industry, which means that these objects are most of the time placeholder objects. In the case of Airbnb, the “reality” of images and their truthfulness is coupled with the quality of the pictures itself and the photo set in general. Differently from the mere descriptive aim of traditional real estate, an Airbnb photo set can include a still life of pottery on a table, a macro of some flowers in the garden, stock images of the neighborhood, or landmarks of the surroundings.

Such practices of value extraction led to the creation of a parallel universe of new professionals and services. Within the users of Airbnb, many are the companies or society that manage a large number of properties offering a range of services addressed to the reservation and the guest stay. From the more practical automated check-in check-out, luggage storage, and transfer from airport to the leisured experiences, and catering services. Many are also the services offered to hosts as the complete management of the properties at all stages, from the online management to the cleaning services, professional photographs, and consultancy. Some of these companies, indeed, propose an advisory service for the housing renewal in order to increase the market appeal, from the website of Dimorra Hospitality, a Napolitan property manager society, “we turn your normal home into a safe source of income.”15

This practice is called home staging, and it is used to carry out projects of modernization or renovation of housing units in order to have higher profits both in the sale or rental. From its denomination, it is evident the willingness to set up a stage for commercial purposes. The practice of home staging is not just house renewal, but more emulation of new aesthetic standards and formal rules conformed to the taste of the global market.

According to an Italian association of home stagers (APHSI), with a home staging renewal, the selling times decrease to about 2/3, and the selling price has a reduction of just 4% compared with the 14% of the traditional selling. The costs of this service, still according to APHSI, is around 1000 euro for an 80 square meters apartment with minor interventions (painting, tidying, photoshoot, and advertisement)16. The costs grow with significant adjustments, like renovation works and furniture purchasing.

Home staging first appeared in the United States during the 1970s, intending to reduce sales times and avoid future discounts on the final price. This practice, even at the time, was nothing new than a small renovation, but the way in which it was promoted and structured, marked another notch in the ecology of housing commodification, reproducing and simplifying existing practices.

In the beginning, home staging was mostly applied in North American middle-class family houses and was a kind of tutorial of how to present and settle the houses to possible buyers, without any structural changes. The real estate agent Barb Schwarz, the first home stager according to her17, in her 80ish promotional video How to prepare your home for sale…so it sells! describes how to settle the house for the buyers, because “the way you live in a home and the way you sell a home are two different things.”18

-

10

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XVf6_rHnE2E [1/06/2020]

-

11

Srnicek, 2017

-

12

https://www.wired.co.uk/article/welcome-to-the-new-reputation-economy. [15/05/2020]

-

13

Further reputational systems introduced by the company are represented by the SuperHost awarding system, and by the verified prime locations for which the company reserved in 2018 the Airbnb Plus section.

-

14

Gallagher 2018

-

15

https://www.dimorra.it. [15/05/2020]

-

16

-

17

Barbara Schwarz holds around a dozen of trademarks related to home staging including The Creator of Home Staging®

-

18

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XVf6_rHnE2E [1/06/2020]

Figure 1. Video stills of Barb Schwarz promotional video “How To Prepare Your Home For Sale…So it Sells”!

Today this practice is present both in the sales and rental market. In particular, this service quickly expanded its popularity to the short-term rental sector due to the facilitated possibility of profit maximization with minimal effort. Indeed, the recognizable fortune of the practice of home staging has been noted (by all odds) by Airbnb. Meridith Baer, one of the leading home stagers in the United States, wrote for the blog of Airbnb, an article in which recommends ten simple tips to improve the house set up and so to “help get more guests and keep them happy.”19From the list, it can be read some functional elements as the hotel-like equipped bathroom and the bedroom with the sitting area; to the application of more ephemeral elements, as flowers, color painting walls or doors, mirrors, and lights.

A typical style is recognizable within Airbnb listings, as highlighted by a research project from AMO presented at the Architecture Triennale of Oslo in 2016, which collected a series of examples from Airbnb listings around the globe where such style is particularly evident. With a series of iconic photographs, they build a taxonomy where the living elements (parquet, wooden tables, white light, and designer furnishings) became the standardized components of staged commodities.

Through the years, this practice became more structured, and within the platform market, the actors became more professionalized. Nowadays, the market of Airbnb is in the hands of the so-called multi-properties hosts –hosts that manage multiple properties– these can be real societies, property managers, other platforms, real estate firms, and even construction firms. In Rome, in 2019, 18% of the hosts own more than three properties accounting for 53% of the stock.20 Those societies propose several additional services to the guests and to the house owners (sometimes these societies are the owner themselves), including home staging.

Across the globe, these companies manage and stage houses to make them profitable assets, letting them flow eventually into the vacation rental market. Some of them, as Homm (owning around 200 properties in Greece), propose in their offers from the renovation of the apartment “use only product of top quality and high-end product brands,”21 to the complete reconstruction from scratch, owning two condo buildings in central Athens. They also propose advisory to the resident permit program Golden Visa; this European program consists of obtaining a 5-year residency permit for non-EU citizens by investing a given amount of money in several assets, including residential property22. Societies as Homm in Athens or Tamea International in Lisbon propose a full package from the sells of the property to the management of it in the case in which the owners want a return on the investment by renting out the property, possibly in the short-term rental market to the benefit of the flexibility and a maximum profit; in these cases, the houses sold are already fully furnished staged commodities ready to enter the rental market.

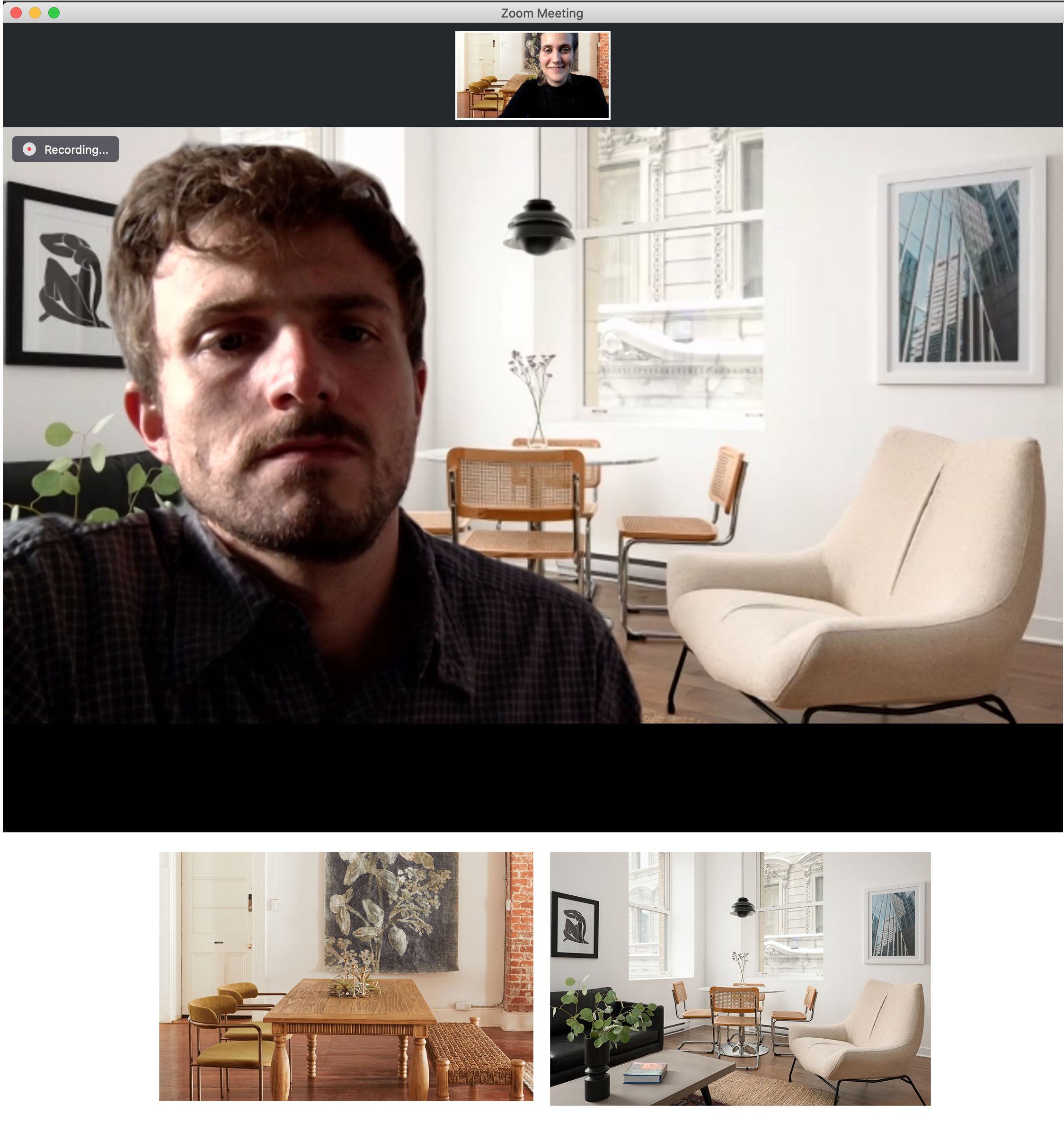

Altido (based in London with around 2000 properties in Europe) in its blog23 recommends how to decorate a small flat meeting the demands of its clients in need to extract as much value as possible from little spaces. While the new real estate unicorn Sonder (based in San Francisco with around 8500 properties across the globe) found its fortune in renting out fashionable designer apartments, the practice of home staging for this company is not a possibility, while a requirement. In a recent article in their blog, they present a series of staged house images made by Sonder interior designers downloadable to be used as Zoom backgrounds.24

-

19

https://blog.atairbnb.com/attract-guests-10-simple-tips-home-staging-expert-meridith-baer/. [15/05/2020]

-

20

Data acquired by AirDNA

-

21

https://www.homm.gr/en/about/. [1/06/2020]

-

22

This program is present in almost every European Country, the investment for a real estate could variate from the 300.000 € in Portugal, 250.000 € in Greece to the 500.000 € in Spain.

-

23

-

24

https://blog.sonder.com/design/introducing-sonder-backgrounds-for-your-next-zoom-meeting/

Figure 2. Screen captures of a Zoom Meeting using the background images provided by Sonder.

“A standard that the commodity has lived up to by turning the whole planet into a single world market”25

The monopoly of Airbnb on the short-term rental market prompted an exponential growth of profitable investments on listings by larger economic enterprises than individuals or families. From a platform devoted to stimulate micro gains for households with a spare room to rent, in a decade Airbnb became a marketplace for high yield investments, involving more and more professionals from the real estate and the building industry.

In this light, these mutations happened across the full spectrum of the hospitality industry. In the post-war globalized world, hotel chains built a wide range of options for the growing middle-classes, setting new standards for aesthetics, comfort, and ultimately for life –the ritual of the modern vacation trip. The revolutionary concept introduced by Airbnb is that the main value of its product profits by the opposite of standardization, as each listing is related to the identity of its host.

Nevertheless, as Airbnb market was set in terms of mass consumption some standards started to emerge globally. Striking similarities between the average two-bedroom flat listing rose from Moscow to New York. Home staging found a mainstream “genre” for its plays, and Ikea contributed greatly as the set designer:

“In some ways the generic Ikea home is almost invisible. It’s repetition. It’s predictability. Its sameness across the globe makes it immaterial. It becomes a predictable nexus from which you choose to explore the city. It, in itself, is not an experience. It’s just the baseline allowing you to sleep. That’s appealing to me because then it is sort of like – what is the minimum investment we can make to see the world? Or to facilitate other people seeing the world? Ikea definitely provides that.”26

Hyggelig is the Danish word describing the kind of aesthetic standard pursued by most of Airbnb listings. The term refers simultaneously to the quality of a domestic space of being nice, and pleasant, and cozy, and comfortable27. It’s interesting to note how a word initially referred to an atmosphere and experiential features was later attached to physical objects constructing an imaginary built upon marketability and profitability.

The domestic space of hyggelig could be related to the urban space of Airspace, a notion introduced by some urban geographers referring to the spatializations of sharing economy –including Airbnb– with their mix of comfort, hisperish minimalism and photogenic corners, where human coexistence is efficiently regulated in time by algorithms28.

In order to respond to the demand of an authentic experience promoted by Airbnb –Belong anywhere™– the practice of home staging provided the tools to combine standardized comfort with marks of personalization.

Once viewed as a whole, the images of staged listings appear to have the twofold characteristic of being generic and unique at the same time. The hyggelig of the white box with wooden minimal furniture unit is marked by signs of local culture here and there. The motto of Airbnb “belong everywhere” unfolds in the paradox of the simultaneous persistence of the comfort of commercial hospitality combined with the uniqueness of lived-in homes decorated with local touches.

-

25

Debord 1970: 19.

-

26

-

27

The word is an extension of the Danish word Hygge. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/hygge [01/06/2020]

-

28

Pavoni and Brighenti (2017)

Figure 3. Details in Airbnb houses. Pictures by the authors.

Diving into the staged interiors reveals how the typical rooms of the modern functional house are subject to slight changes to fulfill this double condition. As this may not be perceivable at first sight, a closer look unveils a slight myopia. A generous kitchen actually equipped with few freebies for coffee and tea making, a bathroom full of towels and some free shampoos but with no sign of cleaning devices, or a living room without a TV filled with posters on the wall showing landmarks of the hosting location. These examples may represent a caricature of the staged home, but they reveal the quintessential aspect of home staging. The emptiest space is filled with the bare minimum necessary objects to provide comfort, while the decorative (low cost) apparatus adds value to the listing in its marketing virtual phase –while having a marginal role during the real experience.

References

-

Beka, I., & Lemoine, L. (2016). Selling Dreams [Documentary]. Beka&Lemoine.

Debord, G. (1970). The society of the spectacle (Reprint). Black & Red.

Farha (2018). Report of the special rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, and on the right to non-discrimination in this context. United Nations Human Rights Council.

Forrest, R., & Williams, P. (1984). Commodification and Housing: Emerging Issues and Contradictions. Environment and Planning, 16(9), 1163–1180.

Gallagher, L. (2018). The Airbnb story: Inside the company disrupting the world.

Iago Lestegás, João Seixas, & Rubén-Camilo Lois-González. (2019). Commodifying Lisbon: A Study on the Spatial Concentration of Short-Term Rentals. Social Sciences, 8, 2.

Harvey, D. (2018). The limits to capital. Verso.

Maak, N. (2015). Living complex: From zombie city to the new communal. Hirmer.

Madden, D. J., & Marcuse, P. (2016). In defense of housing: The politics of crisis. Verso.

Martin, R. (2002). Financialization of daily life. Temple University Press.

Minton (2017). Big Capital. Who Is London For?. Penguin.

Oslo Architecture Triennale, Casanovas Blanco, L. A., Galan, I. G., Mínguez Carrasco, C., Navarrete Llopis, A., & Otero Verzier, M. (Eds.). (2016). After belonging: The objects, spaces, and territories of the ways we stay in transit. Lars Müller Publishers.

Pavoni and Brighenti (2017). Airspacing the City – Where Technophysics meets Atmoculture. AZimuth, V, 10.

Srnicek, N. (2016). Platform capitalism. Polity Press.

Stein, S. (2019). Capital city: Gentrification and the real estate state. Verso.