Nel corso della sua travagliata storia, Berlino ha affrontato diversi cambiamenti strutturali e può essere considerata una città in continua evoluzione. Questo articolo intende analizzare le attuali strategie urbane a Berlino, concentrandosi in particolare sulla cosiddetta Strategia di Berlino 2030. Attraverso una rassegna dei progetti urbani coinvolti nelle diverse strategie, l’articolo mira a presentare i modelli urbani utilizzati per progettare e costruire la nuova Berlino e a discutere criticamente se e in che modo tali modelli saranno correlati alle caratteristiche politiche, economiche e sociali del tessuto urbano.

1. Introduzione

Nel 1910, il critico d’arte Karl Scheffler nel suo libro Berlin: Ein Stadtschicksal (Berlino: il destino di una città) scrisse: «Berlin ist eine Stadt, verdammt dazu, ewig zu werden, niemals zu sein» (Berlino è una città condannata a diventare e mai ad essere). Berlino ha una storia molto travagliata, fatta di continue distruzioni e ricostruzioni in cui le dinamiche politiche ed economiche sono strettamente legate e si riflettono nei cambiamenti fisici. Dalla Guerra dei Trent’anni nel XVII secolo, al cosiddetto Anno Zero, dopo la Seconda Guerra Mondiale, che ha lasciato la città in rovina, Berlino ha sempre dovuto affrontare una rinascita nella sua immagine e nei suoi aspetti fisici. Si può considerare Berlino come un esempio di città multistrato. Tuttavia, i diversi strati e processi di cambiamento sembrano essere più una sorta di giustapposizione di vari immaginari urbani in cui si sovrappongono modelli urbani tabula rasa e progetti. Ogni strato e ogni immaginario rappresentano il cambiamento di un patrimonio politico o economico, ed è per questo motivo che questo documento vuole raccogliere le politiche più rilevanti realizzate nella città in relazione alle trasformazioni urbane dalla caduta del Muro ad oggi.

Un periodo molto particolare e importante per cogliere queste tensioni è l’inizio degli anni ’90, quando il movimento rivoluzionario nella Repubblica Democratica Tedesca (RDT) e la prospettiva di una Germania unita hanno un impatto di vasta portata sullo sviluppo urbano (Schmoll, XXXX). Nel primo decennio dopo la caduta del Muro, Berlino ha subito una trasformazione radicale e uno straordinario boom edilizio a causa della sua necessità di rinascere dalle ceneri della Germania divisa.

Nel corso del tempo, il riferimento a diversi modelli urbani viene utilizzato per definire, costruire e ricostruire l’immagine urbana e per modificare il tessuto urbano al fine di dare continuamente un nuovo volto alla nuova capitale. Infatti, la ristrutturazione delle città occidentali ha dato origine alla diffusione di modelli urbani che sono diventati valori consolidati, considerati desiderabili e realizzabili. Molti architetti coinvolti nella ricostruzione di Berlino erano convinti che le loro opere avessero rilevanza al di là di Berlino: secondo Molnar (2010), la città «offriva un laboratorio per testare possibili scenari per il futuro della città europea in generale nell’era della globalizzazione» (p. 288). In quel periodo Berlino era sotto i riflettori perché aveva la possibilità di immaginare come potesse essere una moderna capitale europea, mentre le altre vivevano nel loro retaggio storico.

Concentrandosi principalmente sui cambiamenti fisici legati alle strategie urbane, l’articolo intende presentare e discutere criticamente i modelli di progettazione urbana attraverso i quali viene progettata e costruita la “nuova Berlino”. Abbiamo innanzitutto esaminato brevemente le principali strategie urbane attuate dopo la riunificazione e i principali progetti attraverso i quali sono state realizzate. Successivamente, ci siamo concentrati sulla strategia urbana più recente, denominata Berlin Strategy 2030, al fine di discutere l’idea stessa di città che ne emerge, come manifesto di ciò che la città vuole diventare e di come può realizzarlo. Come buon esempio di mobilità politica e trasferimento politico (Gonzalez, 2001), le strategie urbane di Berlino, in cui la creazione di immagini urbane è diventata una preoccupazione centrale e l’architettura agisce sempre più come simbolo del “nuovo”, delineano la diffusione di pochi modelli urbani, basati su poche parole chiave (competitività, sostenibilità, creatività, intelligenza), le conseguenze di tale diffusione sui cambiamenti urbani e il flusso di progetti architettonici per ricostruire Berlino.

Alla fine vorremmo mettere in discussione questo atteggiamento internazionale delle città del design attraverso modelli, discutere i pro e i contro, i vantaggi e gli svantaggi che le città subiscono attraverso questo modo di agire.

2. Berlino dopo il Muro: principali strategie urbane

2.1. Una rinascita simbolica: Berlino capitale e la ricerca della «città europea»

Dopo la caduta del Muro e il processo di riunificazione, la prima ondata di strategie urbane è legata alla controversa decisione, presa dal Bundestag (il Parlamento tedesco) il 20 giugno 1991, di trasferire la capitale da Bonn (capitale della Germania occidentale dal 1949 al 1990) a Berlino. Durante questo periodo travagliato, le politiche urbane sono dedicate principalmente a ricostruire Berlino come capitale della Germania unificata, sia fisicamente che simbolicamente. I principali progetti urbani riguardano nuovi complessi edilizi lungo il percorso del Muro e il restauro di strutture ed edifici ancora danneggiati dai bombardamenti della Seconda Guerra Mondiale.

Si verificò una vera e propria “febbre edilizia” che generò il più grande volume di attività edilizia in Europa: «con i suoi 440 cantieri nel centro della città, Berlino si autoproclamò ‘il più grande cantiere d’Europa’” (Molnar, 2010, p. 282). Tuttavia, le strategie urbane richiedono anche un nuovo ruolo di Berlino sulla scena internazionale. Come sostenuto da Molnar (2010), all’inizio degli anni ’90, «slogan popolari (…) descrivevano Berlino come il “centro dell’Europa centrale”, la “porta verso l’Est”, il “crocevia tra Est e Ovest” e la “metropoli europea”. Inoltre, non solo si prevedeva che Berlino avrebbe raggiunto in pochi anni le città globali europee come Londra o Parigi, ma che avrebbe incarnato il modello della metropoli del futuro» (pp. 281-282).

Il piano per la nuova capitale, progettato da Hans Stimmann (direttore dell’urbanistica dal 1991 al 2006 e seguace del movimento del “rinnovamento urbano attento”), mirava a ricostruire il tessuto urbano secondo il modello della “città europea” e una (controversa) “tradizione berlinese”. Skyline orizzontale, piazze, spazi verdi e altri spazi pubblici sono organizzati in una griglia compatta e coerente «per ricostruire la città ottocentesca, intrecciando i frammenti del vecchio e causando una grande distruzione (questa volta della città modernista)» (Molnar, 2010, p. 299). L’obiettivo di Stimmann era quello di agire sulla scala del blocco, introducendo strumenti tecnici di pianificazione (come la sezione stradale e la tipologia residenziale) per stimolare la rinascita della località utilizzando i ruoli della cosiddetta “Ricostruzione critica”, «una strategia formulata all’inizio degli anni ’80 da J.P. Kleihues per il nuovo progetto abitativo per l’Esposizione Internazionale dell’Edilizia (IBA). […] si trattava di un tentativo di rivendicare la tipologia berlinese di isolati e strade con i suoi Mietshaus e cortili come archetipo per tutte le nuove costruzioni della città» (Sauerbruch, 1997, p. 284).

Per gestire i progetti di PostdamerPlaz, Friedrichstrasse e Alexanderplaz sono stati indetti concorsi di architettura e urbanistica per la ricostruzione urbana, basati principalmente sul “modello di città europea”. Tuttavia, questo modello è stato criticato dall’architetto olandese Rem Koolhaas (1991) che, dopo aver lasciato la giuria del concorso per la riprogettazione dell’area di Potsdamer Platz nel 1991 in segno di protesta, ha scritto contro il dogma della tradizionale “città europea”, probabilmente mai esistita. Inoltre, questo modello è stato sfidato anche dal ruolo degli investitori economici globali che, secondo il mantra della città globale, giocano il gioco della concorrenza urbana. Daimler-Benz, Simens, Coca Cola, Allianz, Deutsche Bahn AG sono solo alcune delle 39 società che hanno annunciato il trasferimento della loro sede a Berlino a metà degli anni ’90 (Krätke, 2000). A Postdamerplaz, probabilmente il progetto più rappresentativo di questa tensione, da un lato Stimmann richiede una visione urbana legata alla regolare griglia della Berlino ottocentesca (Boquet, 2007); dall’altro lato, Sony, Daimler Benz Messerschmidt e AAB Group costruiscono le loro sedi seguendo il modello dei quartieri commerciali internazionali. Grattacieli e centri commerciali spiccano nel cuore di Berlino, così come lungo la Friedrichstrasse, ribattezzata la «Quinta Strada di Berlino» (Marcuse, 1998, p. 331).

2.2 Essere globali: Berlino come metropoli dei servizi

Nel frattempo la deindustrializzazione della città procedeva rapidamente e tra il 1990 e il 1996 200.000 persone persero il lavoro nel settore industriale; a Berlino l’era industriale urbana era ormai giunta al termine, come in tutte le altre città europee.

Per rilanciare l’economia, la città ha dovuto puntare su un altro tipo di modello economico. La visione di Berlino come città globale emergente è diventata parte integrante del programma di innovazione e sviluppo tecnologico dell’amministrazione comunale. Concentrandosi principalmente sugli aspetti economici dell’approccio della città globale, questa strategia urbana mira a rafforzare la reputazione di Berlino nel contesto della concorrenza globale attraverso la conversione dell’economia berlinese in una metropoli dei servizi. Questo modello economico si basa sul sostegno finanziario di tutte le industrie che operano nella produzione di servizi, senza affrontare realmente la perdita di posti di lavoro che ha seguito il processo di unificazione e la centralità finanziaria ed economica consolidata di altre città tedesche (in primis Francoforte sul Meno e Monaco di Baviera). Come sostenuto da Krätke (2004), «Berlino non è l’unico centro economico in Germania e la posizione di una metropoli dovrebbe essere empiricamente correlata alle sue capacità economiche in una prospettiva comparativa a livello regionale. Rispetto agli altri centri economici regionali in Germania, Berlino ha una posizione piuttosto debole in termini di capacità di controllo imprenditoriale» (p. 59).

Tuttavia, Berlino ha compiuto alcuni passi per raggiungere lo status di città globale. Il processo di ristrutturazione economica e il desiderio di diventare globale si basano sulla “nuova isola di crescita economica” (Krätke, 2004), legata principalmente alle infrastrutture di trasporto, alle attività finanziarie e ad alta intensità di conoscenza. Infatti, in quegli anni il Senato di Berlino ha finanziato la costruzione del più grande snodo di trasporto d’Europa. La stazione Hauptbahnhof, i cui lavori sono iniziati nel 1995 e che è stata inaugurata nel 2006, è chiamata dai berlinesi la “cattedrale del traffico”. Tuttavia, essa rappresenta anche il simbolo del presunto nuovo ruolo centrale di Berlino nel contesto europeo.

PostdamerPlaz è un altro esempio di questa strategia urbana globale che mira a raggiungere lo status di metropoli dei servizi. Questo quartiere di grattacieli, che ospita le sedi centrali di alcune multinazionali, spicca nel panorama urbano di Berlino come un gruppo di grattacieli raggruppati nel centro della città che definiscono il luogo del nuovo potere economico (Marcuse, 1998). Infine, Adlershof è il polo progettato per seguire le orme del modello di metropoli dei servizi, in particolare nei settori ad alta intensità di conoscenza e orientati all’innovazione come l’industria del software, la biotecnologia e l’ingegneria medica. In questo “parco scientifico e tecnologico” erano situate 1013 aziende e 16 istituti di ricerca (www.adlershof.de).

A prescindere dal carattere simbolico di questi progetti, così come dalla loro funzionalità, per raggiungere l’obiettivo e diventare una vera metropoli dei servizi in azione, Berlino e la sua regione avevano bisogno di più spazio fisico: più uffici, più edifici, più luoghi da costruire. Come sottolineato dal governo cittadino, per promuovere la metropoli dei servizi Berlino aveva bisogno di 11 milioni di metri quadrati di spazi per uffici entro il 2010. Di conseguenza, «un’ondata di acquisizioni immobiliari, conversioni e grandi progetti edilizi interessò in particolare le città e le regioni della Germania orientale, poiché lo Stato tedesco introdusse una speciale regolamentazione di sussidi per gli investimenti immobiliari nell’Est, che prevedeva un regime fiscale di ammortamenti molto favorevole» (Krätke, 2004, p. 61). Questi sussidi furono utilizzati principalmente per facilitare gli investimenti immobiliari nella parte orientale di Berlino. Tuttavia, «nel corso del boom immobiliare, Berlino accumulò il più grande volume assoluto di spazi per uffici sfitti, con oltre 1,5 milioni di metri quadrati nel 1998. Questa cifra diminuì leggermente negli anni successivi; tuttavia, ancora oggi [2004] ci sono più di 1,2 milioni di metri quadrati di spazi per uffici non occupati in città» (ibidem, p. 62). Alla fine degli anni ’90, il boom edilizio si trasformò in un crollo del mercato; la crisi immobiliare si trasformò in una crisi finanziaria. Nel 2001, Berlino entrò in una situazione debitoria, raggiungendo un picco di 65 milioni di marchi. In quegli anni qualcuno definì la crisi come una vera e propria bancarotta della città, poiché vi furono numerosi tagli alla spesa pubblica, specialmente nell’istruzione, nel sistema sanitario e nelle istituzioni di edilizia sociale. Questa crisi proseguì per tutto il primo decennio degli anni 2000.

2.3 Sii creativa, sii Berlino!

All’inizio degli anni 2000 le casse comunali erano vuote e non era possibile mettere in atto alcuna strategia economica per far uscire la città dalla crisi. Ora che i tentativi di lanciare Berlino come metropoli dei servizi o città globale erano falliti, la città aveva bisogno di un altro modello su cui fare affidamento.

Klaus Wowereit, ex sindaco della città, ha deciso di concentrare la nuova strategia urbana sulla cultura, con particolare attenzione alla sottocultura berlinese. Secondo il famoso (e controverso) modello della “città creativa” (Florida, 2003), la nuova strategia urbana si basa «sul presupposto che le città internazionali, tolleranti e in rapida evoluzione abbiano maggiori possibilità di affermarsi nella competizione globale per attrarre le industrie creative» (Lanz, 2013, p. 1312).

I primi investimenti furono destinati agli eventi di massa. La Partner für Berlin GmbH, il partner pubblico–privato ufficiale della città incaricato del marketing urbano e del branding, iniziò a promuovere diversi eventi culturali come la Love Parade, il Carnevale delle Culture, il Christopher Street Day e così via. Successivamente, la svolta culturale divenne il fulcro della campagna urbana Be Berlin!, lanciata dal governo municipale nel marzo 2008 per promuovere la competitività globale attirando le industrie creative, in particolare nei settori della musica, del cinema, della produzione radiofonica e televisiva, dei nuovi media, dell’editoria, del design e delle agenzie pubblicitarie. In effetti, «l’industria dei media è un motore fondamentale dei processi di globalizzazione nei sistemi urbani, dove i cluster dell’industria mediatica agiscono come nodi locali nelle reti globali dei grandi gruppi mediatici. Le imprese mediatiche globali hanno sviluppato reti di localizzazione che si estendono in tutto il mondo e hanno punti di ancoraggio “locali” in diverse regioni e nazioni» (Krätke, 2004, p. 60). Questo nuovo tipo di strategia non portò denaro immediato nelle casse della città, ma accrebbe l’interesse internazionale degli investitori stranieri. Più di 7.000 aziende di creatività multimediale si localizzano a Berlino e nel 2004 la città ottiene il titolo di global media city. «Una nuova agenda di governo iniziò ad affermarsi, che re-immaginava la città come una metropoli internazionale e — come illustrato dal progetto Mediaspree — puntava sul potenziale economico dei milieu creativi che avevano reso la Berlino post-riunificazione un centro globale rinnovato della sottocultura» (Lanz, 2013, p. 1312).

Nel 2002 il Senato di Berlino ha approvato il masterplan del più grande progetto di trasformazione urbana mai realizzato a Berlino, Mediaspree. Il progetto, situato nell’ex zona industriale sulle rive del fiume Sprea, nei pressi dei quartieri di Kreuzberg, Friedrichshain e Treptow, mira a creare un polo mediatico attraverso il completo rinnovamento e l’insediamento di hotel, residenze di lusso, centri commerciali, uffici e sedi delle grandi aziende coinvolte (Universal Music, MTV, Mercedes-Benz). Come scritto da Lanz (2013), il progetto Mediaspree consiste in «180 ettari di immobili nel centro della città destinati a essere trasformati in un denso cluster di industrie creative con un appeal globale» (p. 1310). Il progetto era in forma di partenariato pubblico-privato perché le casse della città erano ancora in una situazione difficile, quindi l’aiuto privato ha reso possibile il progetto, ma dall’altra parte ha reso l’interesse privato più rilevante rispetto al bisogno pubblico. Infatti, il progetto Mediaspree ha avuto molti problemi con la comunità urbana più vicina, che lotta per avere più spazio per la città che per le aziende private che vi sono allocate.

Con il progetto Mediaspree e il rafforzamento del cluster Adlershof, Berlino potenzia il proprio ruolo: da polo di attrazione a produttore di servizi e beni culturali. Grazie a ciò, la città è uscita dalla crisi. Tra il 2005 e il 2012 il tasso di crescita medio è stato del 2,5%, mentre nel resto della Germania era dell’1,5%; tra il 2006 e il 2013 sono stati creati più di 200 mila nuovi posti di lavoro, quindi la percentuale di disoccupazione è scesa dal 17% al 9,9% (Krätke, 2000). Il modello di città creativa stava dando i suoi frutti e nel 2014 Berlino è stata nominata World Media City.

Come in altri progetti della Berlino post-Muro, anche nel caso di Mediaspree le architetture devono essere i segni iconici del nuovo sviluppo urbano. Dalla lunga serie di grattacieli situati sulla riva dello Spree a quelli di Potsdamer Platz, da Alexander Platz fino alla “cattedrale del traffico” di Hauptbanhof, edifici adibiti a uffici e residenziali, centri commerciali, musei, gallerie, hotel segnano lo spazio urbano come simboli di un nuovo potere economico e come attrazioni per turisti e investitori. La nuova architettura «produce spazi per uffici, celle ammucchiate in forme che non variano molto: qualche forma cubica, se possibile una torre, la griglia è ancora l’elemento base della costruzione, anche se queste forme ora possono essere contorte, girate, arrotondate, inclinate o tutte queste cose insieme. Le forme esterne sono trasformate in qualcosa di interessante e spettacolare (…) Quello che otteniamo è un’architettura per l’intrattenimento» (Steinert, 2009, p. 286).

3. Ritorno al futuro: la strategia di Berlino per il 2030

Nel 2013, il Senato di Berlino ha pubblicato una prospettiva per definire le linee guida per le ulteriori trasformazioni di Berlino da realizzare entro il 2030. La Strategia Berlino 2030 delinea alcune parole chiave come punti fermi della strategia: “il rapporto sullo stato attuale ha fornito un’analisi approfondita basata su una serie di idee, piani strategici e politiche future volte a gettare le basi per lo sviluppo strategico di Berlino” (Strategia Berlino 2030, p. 6).

Per sviluppare il concetto della strategia è stata creata una piattaforma di consultazione pubblica denominata City Forum 2030; oltre 2500 cittadini sono stati coinvolti per esprimere le loro opinioni sul futuro della città. Per coinvolgere la comunità sono stati utilizzati strumenti quali workshop, dibattiti pubblici locali, progetti scolastici e il cosiddetto “telegramma di Berlino” (come post su Twitter e Facebook, e-mail e lettere). Tutti i contributi sono stati analizzati e discussi dalle amministrazioni del Senato, dalle autorità locali e dagli specialisti per elaborare la strategia attuale.

Il programma definisce le parole chiave dello sviluppo futuro, ovvero i concetti su cui si baseranno tutti i progetti futuri; sette strategie che indicano gli obiettivi prioritari della città; infine dieci aree di trasformazione caratterizzate da un progetto principale o da piccoli interventi di adeguamento urbano.

Le parole chiave che dovrebbero guidare la trasformazione della città sono: il concetto di intelligenza e creatività, per mantenere il suo carattere dinamico e cosmopolita e continuare ad essere creativa e culturalmente attraente per le persone e gli investitori privati; essere verde, autosufficiente, autonoma dal punto di vista energetico con l’aiuto delle nuove tecnologie e, infine, raggiungere l’obiettivo finale di diventare una città a impatto ambientale zero entro il 2050; il “leggendario mix berlinese” (Berlin Strategy 2030, p.8), quell’aspetto che ha reso Berlino una metropoli tollerante e multiculturale, dovrebbe continuare a funzionare a livello di quartieri, comunità e vita sociale degli abitanti.

Con queste parole chiave, la strategia attuale si basa su sette punti principali su cui investire. Tali strategie promuovono uno sviluppo sostenibile per la città fino al 2030, dalla qualità della vita al potenziale competitivo: “le strategie forniscono obiettivi di sviluppo concreti, identificano i campi d’azione appropriati per il lavoro collaborativo e definiscono una visione chiara di ciò che Berlino avrà realizzato entro il 2030” (Strategia di Berlino 2030, pag. 24). Ecco le sette strategie:

- economia della conoscenza intelligente: promuovere le start-up e le relazioni tra istituti di ricerca e attività economiche, sostenere i poli tecnologici;

- creatività: migliorare e aumentare i luoghi di produzione culturale, mantenere e sviluppare spazi e locali per artisti e imprese creative e culturali, sostenere la diversificazione spaziale della domanda turistica e organizzare eventi culturali di massa;

- istruzione: fornire infrastrutture scolastiche di alta qualità, migliorare gli asili e le scuole elementari, aumentare il livello dell’istruzione e garantire un buon posto di lavoro dopo gli istituti di istruzione tecnica;

- diversità dei quartieri: sostenere la città sociale attraverso l’aumento degli spazi pubblici e abitativi e la salvaguardia delle attività locali, come negozi e servizi;

- verde: collegare gli spazi liberi e verdi, ripensare l’ulteriore sviluppo infrastrutturale come sotterraneo e procedere a uno sviluppo attento dell’ambiente urbano;

- clima: orientare il rinnovamento del patrimonio immobiliare e la costruzione di nuovi edifici verso l’efficienza energetica, aumentare l’utilizzo delle energie rinnovabili, attrarre tecnologie urbane come le aziende di “tecnologie pulite”;

- accessibilità e mobilità: rendere più attivo il trasporto pubblico, aumentare le piste ciclabili e pedonali e promuovere nuovi modi di mobilità sostenibili, come i veicoli elettrici.

L’ultima parte del documento illustra le aree di trasformazione seguendo le linee tracciate dal concetto delle parole chiave e dalle strategie d’azione. Dalla prospettiva sono emersi dieci nuovi poli di trasformazione urbana. Ogni area selezionata è caratterizzata da un nuovo progetto o da una strategia di pianificazione urbana. I poli sono distribuiti in tutta la città, dalla periferia al centro, per enfatizzare e mantenere il carattere multicentrico di Berlino. Questi progetti sono concepiti come pietre miliari per l’ulteriore sviluppo di quell’area, per innescare il motore di un rinnovamento urbano o di una nuova area di urbanizzazione. Nel documento, questi sono chiamati “stimoli”, proprio per stimolare l’ulteriore cambiamento di quella parte della città, “le aree di trasformazione offrono un potenziale di sviluppo rilevante per l’intera città sia in termini di questioni sociali che di spazi aperti” (Strategia di Berlino 2030, p.58).

Fig. 5 – Strategia di Berlino 2030 “Stimulus”

I dieci poli di trasformazione sono: Mitte, il centro città con il progetto dell’Humboldt Forum, il nuovo centro culturale; City West, che rafforza il suo ruolo di vetrina globale della città; Stedtspree e Neukölln con l’intenzione di ampliare il progetto Mediaspree; Wedding con la sua nuova area residenziale e commerciale Europacity; Berlin Tegel, la nuova sede per imprese, aziende e start-up; la città vecchia di Spandau; Adlershof e il suo polo tecnologico; il Südwest, che migliora le strutture della Freie Universität e promuove un incubatore di imprese; Marzahn-Hellersdorf, che lavora sulla grande area verde che circonda Berlino; e infine Buch, con l’intenzione di renderlo il prossimo luogo popolare e attraente in cui vivere.

I progetti più significativi e rilevanti sono: Europacity, un quartiere completamente nuovo vicino alla stazione centrale di Hauptbhanhof, l’Humboldt Forum, un centro culturale nel centro della città, la prosecuzione del piano regolatore Mediaspree e la conversione dell’aeroporto di Tegel in un nuovo centro di ricerca per le start-up, come nuovo polo scientifico e tecnologico (e quindi la costruzione di un nuovo aeroporto).

Dietro la grande stazione centrale di Hauptbhanhof, è rimasto vuoto un enorme spazio tra il fiume; lì il piano Berlin Strategy 2030 prevede un nuovo quartiere che includerà residenze, servizi e uffici, chiamato Europacity.

L’area ospiterà 1200 unità residenziali, in edifici che rispettano i limiti di altezza stabiliti da Stimmann nei primi anni ’90, un campus artistico, un porto turistico, ristoranti, negozi, uffici, una grande quantità di spazi pubblici e un “invitante lungofiume” (ASTOC Studio, 2008). Vicino alla stazione sorgerà un nuovo quartiere di grattacieli, dove saranno situati gli uffici; saranno poi costruiti tre nuovi ponti che collegheranno le due rive; gli edifici commerciali sorgeranno sui due lati della ferrovia per attenuare l’inquinamento acustico nella zona residenziale.

Questo progetto sarà la prima impressione di tutti i turisti che arriveranno dalla stazione Hauptbahnhof, per questo motivo assumerà un significato particolare: sarà l’immagine della città, il suo specchio. Sarà quindi una città attenta al verde (grazie ai numerosi spazi pubblici e parchi), alla cultura (il campus artistico), all’economia (gli edifici adibiti a uffici) e ai turisti (grazie al percorso sul lungomare e al porto turistico); sarà quindi una città che riflette tutti quegli standard globali che la rendono interessante, attraente, contemporanea e invitante. “Il quartiere urbano sarà, in futuro, la prima impressione di Berlino per milioni di visitatori. È quindi un importante ‘biglietto da visita’ per la capitale” (www.german-architects.com).

Fig. 6 – Masterplan Europacity

Il secondo progetto incluso nella Strategia di Berlino riguarda l’intervento su un edificio storico come nuovo centro culturale. L’edificio, situato nell’Isola dei Musei nel centro della città, era il Palazzo della Città durante l’Impero prussiano e, dopo la seconda guerra mondiale, anche se riportò danni minimi, fu distrutto per diventare il socialista Palast der Republik, il palazzo del parlamento della Germania dell’Est e il centro civico e culturale della capitale. Nel 2006, dopo alcune controversie al riguardo, l’edificio è stato nuovamente demolito per dare vita al nuovo Humboldt Forum. Il progetto ripristinerà la forma originale dell’edificio prussiano e ospiterà un museo, una biblioteca e alcuni dipartimenti universitari, incarnando il centro culturale dell’area interna della città. Ciò che troviamo qui è la volontà di mantenere la tensione del centro storico, nella forma del “vecchio” e nelle strutture del “nuovo”.

Considerando il successo e il buon funzionamento del polo scientifico di Adlershof, il Senato di Berlino ha deciso di proporre un altro polo tecnologico nella città, questa volta per investire in una sorta di incubatore di start-up. A Berlino, il modello di business delle start-up ha già dato buoni risultati, come SoundCloud e Reserch Gate, entrambe nate a Berlino nel 2008; questo tipo di modello potrebbe dare la possibilità alle giovani associazioni di creare la propria azienda.

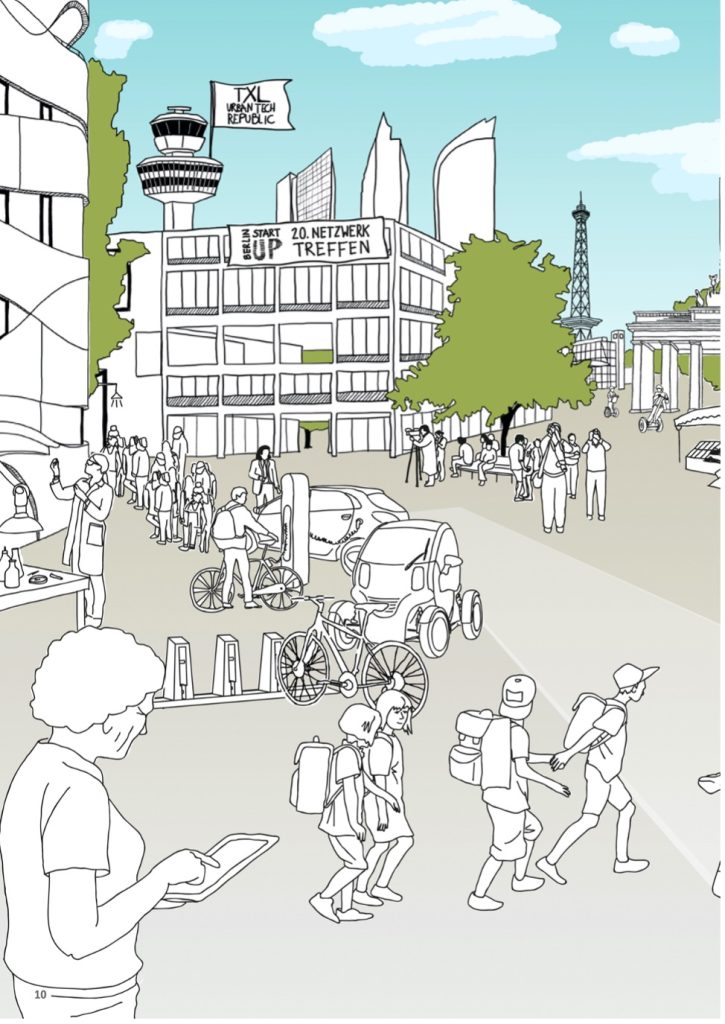

Il nuovo hub sarà situato nel sito dell’attuale aeroporto di Tegel; infatti, l’intero progetto prevede innanzitutto la costruzione di un nuovo aeroporto, più grande di quello attuale, che servirà tutta la regione del Brandeburgo e competerà con quello di Francoforte sul Meno per la gestione del traffico aereo internazionale; successivamente, Tegel sarà convertito in sede dell’hub. Il cluster si chiamerà Urban Tech Republic e così anche il nuovo polo di ricerca “sarà un centro di eccellenza per le tecnologie urbane, tra cui l’ingegneria automobilistica, le scienze della vita, l’energia (tecnologia) e le tecnologie dell’informazione e della comunicazione” (Berlin Strategy 2030, 2015).

Grazie alla sua posizione, il progetto sarà il motore di una nuova urbanizzazione dell’area circostante, per orientare consapevolmente l’espansione della città. L’intera area ha una superficie di 460 ettari e comprenderà un nuovo centro residenziale, ospiterà più di 800 aziende, un dipartimento universitario e un istituto di ricerca; saranno creati 15.000 nuovi posti di lavoro e 5.000 studenti frequenteranno l’università al suo interno “una rete funzionante di università, strutture di ricerca e aziende manifatturiere sta sviluppando soluzioni per una città intelligente” (ibidem.).

Il percorso di sviluppo tracciato dalla Strategia di Berlino 2030 evidenzia una strategia in evoluzione in materia di economia, politiche urbane e sviluppo urbano. Grazie alla sua situazione economica positiva, Berlino è ora in corsa per entrare nella rete globale delle città attraenti e, per riflettere un modello specifico, ha cambiato la sua forma fisica.

Fig. 7 – Schizzo della TXL Urban Tech Republic

4. Progettazione urbana tramite modelli?

Dalla “città europea” a quella creativa, dal mito di essere una città globale alla nuova città verde e sostenibile, le strategie urbane della Berlino post-muro si basano su alcuni modelli urbani disgregati. Le politiche economiche globali costringono le città ad uniformarsi fisicamente l’una all’altra per rispondere alle esigenze del mercato, del turismo e degli investitori che vogliono vedere ciò che si aspettano di vedere, gli spazi che si aspettano di percorrere e le esperienze che si aspettano di vivere. Tuttavia, una città può essere progettata per riflettere un modello economico? I modelli economici sono in grado di fondersi nella complessità urbana o rimangono solo un’espressione economica? Infine, i modelli di trasformazione urbana sono in grado di affrontare le dinamiche in continua evoluzione di un tessuto urbano specifico?

Negli ultimi decenni, le innovazioni e i cambiamenti urbani sono stati confezionati come modelli che possono essere distaccati ed esportati in luoghi diversi. Nello specifico, il mix tra imprenditorialità statale da un lato e sviluppo di infrastrutture sostenibili dall’altro ha generato una serie di ricette di innovazione urbana che promuovono condizioni e stili di vita urbani “di successo”. I modelli urbani replicabili sono diventati nuove urbanità invocate, invidiate ed esemplari. I modelli urbani sono utilizzati in tutto il mondo per risolvere i problemi urbani – ad esempio, edilizia popolare, sviluppo dei centri cittadini, industrie pulite, quartieri di lusso, attrazioni culturali e turistiche – e per trasformare i luoghi urbani in città di livello mondiale, città creative, città intelligenti e così via.

Questo atteggiamento globale è definito policy transfer, e le pratiche utilizzate «riguardano il processo attraverso il quale la conoscenza relativa a politiche, assetti amministrativi, istituzioni e idee in un sistema politico (passato o presente) viene utilizzata nello sviluppo di politiche, assetti amministrativi, istituzioni e idee in un altro sistema politico» (Dolowitz e Marsh, 2000, p. 5). Questo tipo di scambio di politiche rappresenta un vero mercato economico in cui gli Stati, e in particolare le città, comprano e vendono modalità di amministrazione urbana. Seguire la “buona pratica” o imparare dal “modello di successo” rimuove la responsabilità politica dei governi locali rispetto alla gestione contestuale e specifica del territorio. L’illusione di avere una “best practice” applicabile in qualsiasi contesto urbano, funzionante in qualunque sistema economico e sociale, sta appiattendo drammaticamente le città. Ogni città è smart, ogni città è creativa, verde, sostenibile, e così ogni città svilupperà progetti per rendere possibili tali immagini. Questo import–export di politiche è direttamente connesso al contesto urbano, che diventa il principale palcoscenico di applicazione, «poiché alcune città acquisiscono uno status paradigmatico o da celebrità in quanto sembrano riassumere un’epoca, il luogo in cui tutto converge» (Thrift, 1997, p. 142, cit. in Gonzàles, 2011, p. 2). Così, la domanda turistica di Bilbao ha portato alla politica di rinnovamento della cosiddetta McGuggenheization, che consiste nel sostenere l’economia turistica di una città attraverso il modello museo–più–archistar; oppure la necessità di riutilizzare il porto industriale che, per la prima volta a Baltimora negli anni ’80, ha introdotto il modello del waterfront; o ancora le politiche verdi che hanno fatto esplodere le pratiche di urban gardening.

Come insieme sintetico di forme urbane desiderabili e realizzabili, questi modelli sono stati concepiti dall’immaginazione di urbanisti e sviluppatori e concretizzati in forme edilizie a Berlino (come in altre città occidentali). Da un lato, essi rappresentano un punto di riferimento simbolico delle aspirazioni urbane; dall’altro, forniscono progetti realizzabili per la riqualificazione urbana. I modelli urbani non sono solo una tecnologia per costruire città globali e centri di conoscenza altrove, ma possono diventare uno strumento politico per cambiare la forma costruita e lo spirito sociale dell’ambiente urbano. La modellizzazione urbana viene quindi utilizzata come strumento per rimodellare l’ambiente urbano e la socialità, nonché per rendere alcune parole chiave generiche – sostenibile, vivibile, creativo, globale, intelligente – i nuovi criteri per progettare e costruire le città.

Anche se questo modo di costruire le città sta già diventando globale, le città sono caratterizzate da una complessità che non può essere risolta sostituendo le “migliori pratiche” da un contesto all’altro. La falla nel sistema di trasferimento delle politiche risiede nella sua non specificità: esso descrive il modo migliore per risolvere un problema, ma non nel proprio contesto. Il modo in cui la città reagisce all’applicazione del modello è, in un certo senso, il modo in cui cerca di mantenere la propria complessità, ed è per questo che “non è stato, è importante sottolinearlo, un preludio all’omogeneizzazione” (Peck, 20011, p. 9).

Tornando a Berlino, ripercorrendo la sua storia attraverso modelli e politiche sostituibili, è possibile osservare come la città abbia reagito a tali modelli e politiche, talvolta rifiutandoli, come nel caso del tentativo di trasformare Berlino in una città globale, talvolta assorbendoli, come nel caso delle politiche creative urbane. Prendendo Berlino come caso teorico, si può supporre che noi, in qualità di pianificatori, ricercatori o semplicemente abitanti, dovremmo considerare la città come “un sistema complesso e incompleto” (Sassen, 2016), un sistema aperto in cui domande e risposte non possono essere assolute e statiche. In questo modo, la definizione di Scheffler di Berlino, una città condannata per sempre a diventare e mai ad essere (1910), potrebbe essere un approccio paradigmatico allo studio e all’amministrazione delle città.

Riferimenti

Berlin strategy 2030, Urban development concept, 2015, Senate Department for Urban Development and Envirorment

Dolowitz D.P. and Marsh D., 2000, Learning from Abroad: the Role of Policy Transfer in ContemporaryPolicy-Making, Gover- nance: An International Journal of Policy and Admainistra- tion, vol. 13, pp. 5-24

Florida R., 2003, Cities and Creative Class, City & Community, vol. 2(1), pp. 3-19

Gonzàles S., 2011, Bilbao and Barcelona ‘in Motion’. How urban regeneration ‘Models’ travel and Mutate in the Global Flows of Policy Tourism, Urban Studies, vol. 48(7), pp. 1397-418

Gonzàles S., 2011, Bilbao and Barcelona ‘in Motion’. How urban regeneration ‘Models’ travel and Mutate in the Global Flows of Policy Tourism, Urban Studies, vol. 48(7), pp. 1397-418

Krätke S., 2000, Berlin: The Metropolis as a Production Space, European Planning Studies, vol. 8(1), pp. 7-27

Krätke S., 2004, Economic Restructuring and the Making of a Financial Crisis – Berlin’s Socio-Economic Development Path 1989 to 2004, disP – The planning Review, vol. 40 (156), pp. 58-63

Lanz S., 2013, Be Berlin! Governing the City through Freedom, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 37(4), pp. 1305-24

Marcuse P., 1998, Reflection on Berlin: The Meaning of Construc- tion and the Construction of Meaning, Joint Editors and Blackwell Publishers Debates, pp. 331-8

Molnar V., 2010, The Cultural Production of Locality: Reclaming the ‘European City’ in post-Wall Berlin, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 34(2), pp.281-309

Peck J., 2011, Geographies of Policy: from Transfer-Diffusion toMobility-Mutation, Progress in Human Geography, vol. 35(6), pp.773-97

Sassen S., 2016, Urban Age Shaping Cities: Global capital and urban land, La Biennale di Venezia conference

Sauerbruch M., 1997, Berlin 2000: a missed opportunity, The Journal of Architecture, vol. 2(3), pp. 283-9

Scheffler K., 1910, Berlin: Ein Stadtschicksal, Suhrkamp, 2015, Berlin

Schmoll, XXXX

http://www.adlershof.de/

http://www.astoc.de/

http://www.german-architects.com/

Crediti immagine:

Fig. 1 – © Chiara Iacovone, 2016

Fig. 3 – www.beberlin.de

Fig. 4 – www.morgenpost.de

Fig. 5 – Strategia di Berlino 2030, Concetto di sviluppo urbano, 2015, Dipartimento del Senato per lo sviluppo urbano e l’ambiente

Fig. 6 – www.german-archiect.com

Fig. 7 – Strategia di Berlino 2030, Concetto di sviluppo urbano, 2015, Dipartimento del Senato per lo sviluppo urbano e l’ambiente